"What on Earth?"

Article by Ray Barbehenn. Photos by Ray Barbehenn and Richard Stromberg

Seeds are made to be spread around. Their parents need them to be dispersed, both to avoid competing with each other for resources and to have a chance at colonizing new places. They move in many different ways. Some seeds are blown by the wind. Some are hidden inside sweet fruit and are spread in animal droppings. Some are carried off and buried in the ground by animals such as squirrels. Others attach themselves to passing animals, as hikers know well.

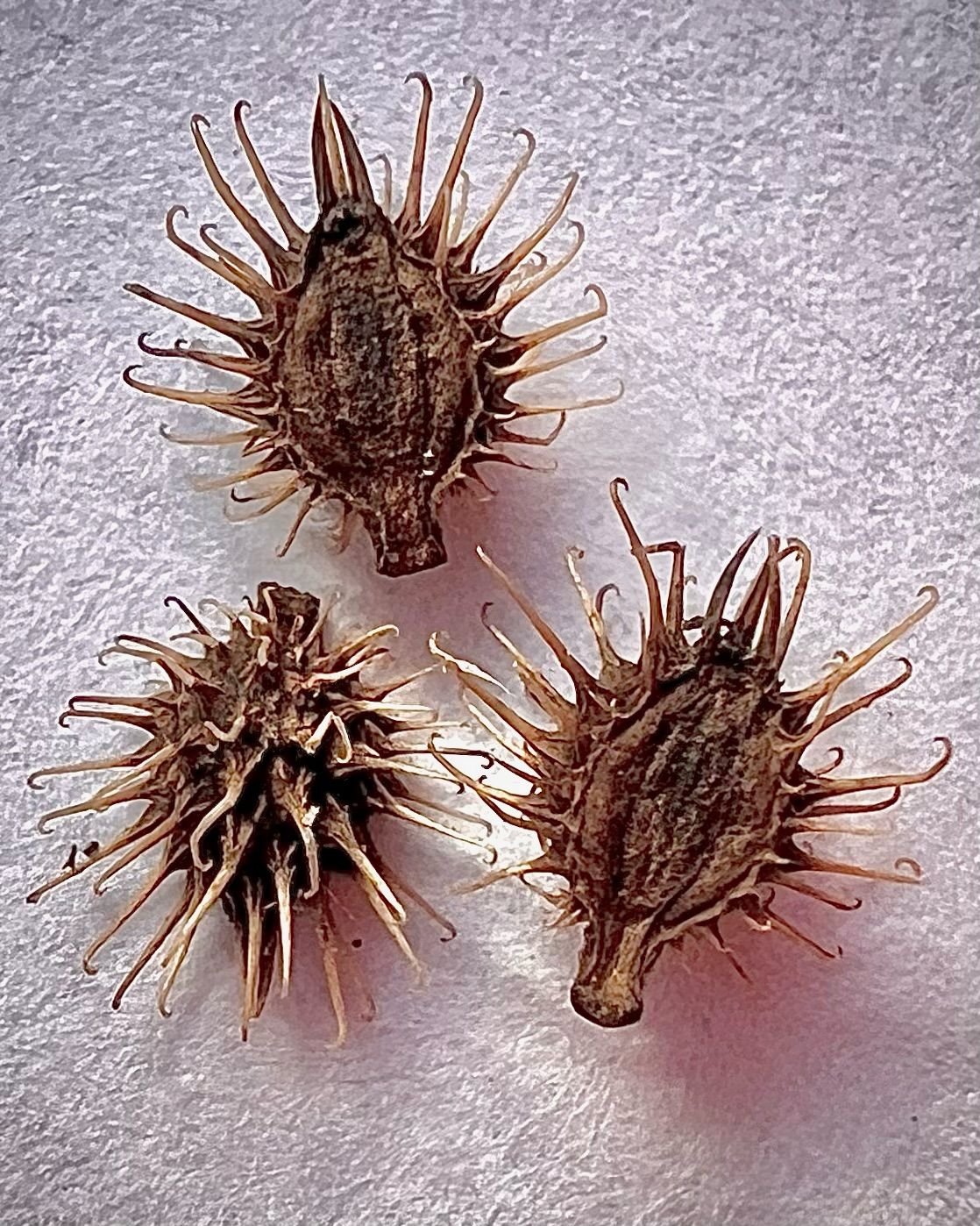

The left photo shows the seeds of Canadian Black Snakeroot (hereafter just "Snakeroot"). I removed these from my pants in late October in Duke Hollow (northern Virginia near the AT). They were about a quarter-inch long, including the bristles. Each Snakeroot flower produces two seeds; you can see their flat, inner sides where two in the photo have split apart. Also notice the hooks on the bristle tips. The right photo shows a pair of the half-inch-long seeds of Aniseroot. These banana-shaped seeds were still delicately attached to a stem that was picked in mid-October in Duke Hollow. They also formed in a single flower and then split apart as the seeds matured. This was their final resting position, where they waited for the right force to disperse them.

How are the seeds of Snakeroot and Aniseroot spread?

A. Snakeroot seeds are attached to animals and Aniseroot seeds are blown by the wind.

B. Snakeroot seeds are blown by the wind and Aniseroot seeds are attached to animals.

C. The seeds of both species are attached to animals.

D. The seeds of both species are blown by the wind.

Fun Facts and Musings

The seeds of Snakeroot and Aniseroot make their intentions clear when they get stuck on our clothes or in our dog's fur. A look at the details of their structures shows how they have become good at being dispersed by animals. The seeds of Snakeroot are little balls, mostly surrounded by hooked spines. This is a common burr shape. Each little hook is part of a team effort to resist being pulled back out after the burr becomes entangled in fur. By comparison, the elongated, pointed shape of Aniseroot seeds lets them penetrate more deeply into fur (or socks). Instead of clinging with numerous hooks, they resist being pulled back out with many tiny barbs. (See top photos.) They are little harpoons! Presumably, their delicate attachment to the stem makes it easy for them to be released into the fur of passing animals.

If you look through the huge gallery of seeds from around the world at

https://seedidguide.idseed.org/gallery/, you can see that dispersal on animal fur is not a common strategy for seed movement. Indeed, less than 5% of seed-bearing plants produce burrs (Those species that do make burrs make a big impression on us!).

It is much more common for "weedy" plants, such as Dandelions, to make seeds that are blown by the wind, rather than sticking to animals. Perhaps this is because the wind is a more consistent force than collisions with animals. Animals also can have a tendency to concentrate burrs along paths, producing a narrower distribution than the wind. On the positive side, animals tend to carry seeds greater distances than the wind.

Different environmental conditions can also favor the success of burrs. For example, burrs may be dispersed better than wind-blown seeds in the woods, where the wind is relatively weak. In open fields, one might expect the opposite – that plants with wind-blown seeds do better than those with burrs.

What features make a really good burr? First, there is the way a burr interacts with its animal carrier. A good burr needs to have the right balance of being clingy, but also being readily removed. A good burr must not be too tightly attached, such as in the matted fur of an ungroomed dog, or it might never come back off! Instead, a good burr might allow an animal's contact with woodland vegetation to brush it off. (The scattered distribution of Aniseroot plants throughout the woods suggests that their seeds do fall back off of fur easily.) It would probably benefit a plant if its burrs were annoying enough that the carriers eventually notice them and groom them off. On the other hand, if a plant's burrs were too annoying, they would be removed quickly and not dispersed at all. For example, burrs with long needle-like spines might become anchored well on an animal, but if they were painful they might be groomed off immediately. A good burr needs to be a little stealthy.

Thus, the success of a burr depends on its size, weight, and, importantly, the number, length, and shape of its hooks or barbs. These are the little details that determine how readily burrs get stuck to, and unstuck from, animal fur. Even the position of burrs on a plant affects their likelihood of getting picked up by a passing animal. A good burr is tick-like – sitting at a height on a plant that an animal is most likely to brush against. Mid-calf is a very popular height for both.

Snakeroot and Aniseroot are in the carrot family. Not surprisingly, Wild Carrot (or Queen Anne's Lace) also has seeds that can act like burrs. But, Wild Carrot seeds are not fully committed to clinging to animals; some are blown away by the wind! The details of this mixed strategy are unusual. During damp weather, mature Wild Carrot seed heads close up like fists, with all the seeds held tightly inside. However, when the seed heads are dry, they spread open, exposing the seeds. Dry, low humidity conditions are common in the winter, when some of the spiny seeds are blown free by the wind and roll across crusty snow fields like tiny tumbleweeds.

Common Burdock (bottom photo) is an example of a member of the aster family with animal-dispersed seeds. Numerous hooked spines on the tips of the "bracts" completely surround the bases of the flowers. This plant was found by Richard Stromberg at Two-owl Farm (in the foothills east of the Blue Ridge in northern Virginia) on August 5, 2023. After the seeds have matured, each ball-shaped structure turns brown and is easily detached from the plant onto fur or clothing. The seeds themselves don't have hooks. They rely on the whole seed head getting carried away by an animal.

Velcro was inspired by a relative of Burdock: Cocklebur. Velcro's name is a combination of two French words: velours (velvet) and crochet (hook), representing the two sides of Velcro. Inventing Velcro may have been inspired by a burr, but it took Velcro's inventor nearly ten years of trial and error to arrive at a functional product. After all, Cocklebur burrs do not have to be repeatedly ripped off a fabric and remain functional for years! Perhaps someone could make a different fastening mechanism by copying Aniseroot seeds?

"What on Earth?" Answer

Answer: C!

Thanks to Richard Stromberg for identifying the seeds of the Canadian Black Snakeroot! Send your photos and ideas for topics to Ray at rvb@umich.edu.