The Shenandoah National Park is one of the most beautiful parks in the world. While it was proposed as early as 1925, it was not officially dedicated until 1936. The Park area extends from the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains down the east and west slopes towards the foothills between Front Royal, Virginia and Waynesboro, Virginia. The one hundred and five mile long Skyline Drive extends along the upper reaches of the Blue Ridge through the park area between Front Royal and Waynesboro. A highway named the Blue Ridge Parkway connects the south entrance of the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia with the north entrance of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park in Tennessee.

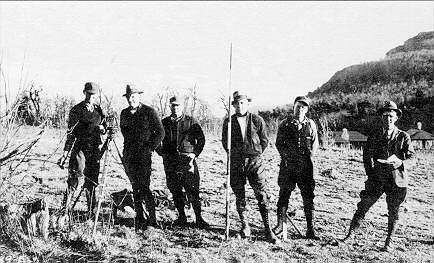

In January of 1931 I was one of the first party of men employed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Public Roads to prepare surveys and design plans needed for construction of an access road from the village of Creiglersville, Virginia, up the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountain to President Hoover's Camp on the Rapidan River, which became the forerunner of the Skyline Drive. Our field office consisted of a canvas tent mounted on a wooden platform located on a vacant lot in the village. As it was bitterly cold, we had a small kerosene space heater on the floor and for light we had two gas fired table lanterns.

A few days after my arrival, we began the surveys and completed them to Hoover's Camp by early spring, 1931. About that time the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Interior, along with Governor Byrd of Virginia, convinced President Hoover and the U.S. Congress to build what was then being referred to as the "Skyline Drive" to be located in the Shenandoah National Park. Construction of the road from Creiglersville to Hoover's Camp was then canceled and we were directed to continue the necessary surveys from Hoover's Camp up the east side of the Blue Ridge to the top of the mountain at the Big Meadows area where it could connect with the Skyline Drive when built. That we did and the road from Creiglersville to Hoover's Camp was never built.

We completed our work to Big Meadows at the top of the mountain by late spring of 1931 and were then directed to continue northward from there via the Skyland Summer Resort and on to Panorama at the Lee Highway (a- distance of about twenty-five miles) which was the real beginning of the Skyline Drive.

There was a problem that had no direct connection with the building of the Skyline Drive, but it is most worthy of note. A killing blight of the chestnut tree forests dominated the upper reaches of a great portion of the Blue Ridge Mountains,especially in the Big Meadows and surrounding areas during the fall and winter months of 1931-32. Prior to that blight there were hordes of chestnut trees growing in numerous areas of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In fact there were so many chestnut trees growing in the wild that many of the people in those areas gathered chestnuts by the bushel basketfuls and carted them to Luray or other railroad sidings in the Valley where they could be loaded on railroad freight cars for shipment to markets when they were loaded.

However, all of that came to a sudden end when the chestnut tree blight of 1931-32 arrived. It just seemed that all of those trees died at the same time and no one knew how to prevent it. It was a sad sight to behold. Every tree was completely stripped of all it's foliage, including all the bark and leaves. The completely barren trunk and limbs of each and every one of those trees was left standing in it's barren state for a long period of time, which was a constant reminder of their demise throughout the entire area by any and all persons who observed them. To those of us working in the area the saddest part of all was our memory of the numerous times we paused to eat some of those delicious chestnuts during the preceding season.

The number of our design engineers and field survey crews increased as we approached the Skyland Summer Resort area in late fall of 1931 when it was considered necessary to move our office and living quarters closer to the work.

The Skyland Resort was located above the three thousand foot level near the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains just south of Stony Man Mountain and was owned and operated by Mr. George Freeman Pollock. The Resort provided the ideal location for our move but it had been designed and built for summer use only. It consisted of a number of wood, slab-faced cabins, each with a living room with fire place and from two to four bed rooms, a bathroom and electric lights. Water was piped above ground by gravity from a spring on Stony Man Mountain via an "above ground" reservoir and on to the individual cabins. Following careful study, it was agreed by all that certain reasonable operational changes would make the Resort acceptable for our use through the coming winter. When those changes were made we moved in.

Due to the extremely cold winter weather the water system and the cabin bathrooms were off limits during our stay. Instead, we had a large dining room and a large bathroom with showers, with each unit centrally but individually located in the camp area. Water for those two facilities was hauled in as needed. The only heat in the cabins was from the living room fire place, with fire permitted only when occupants were present, but completely extinguished before retiring. Also, no fire was permitted in the mornings before leaving for work. That meant dressing in the cold and walking outdoors from the cabins, to and from the dining and bath facilities. Of course the bedrooms were as cold as the outdoors but we had lots of blankets.

Most mornings we found the top edge of the blankets frozen solid where we had breathed on them during the night and it took a lot of willpower to get out of those beds.

Once settled in our new quarters we returned to our office design and field survey work from Skyland northward toward Panorama. Those of us working in the field then had to walk to and from work every day carrying all of our equipment and supplies, leaving home at daybreak and returning at dusk. We worked twelve to fifteen hours a day during that fall and winter. Most of the men selected for that work were between twenty and thirty years of age and most capable of accepting the hardships involved.

Prior to opening Skyland for the 1932 summer season we had extended our preliminary surveys northward about halfway from Skyland toward Panorama when we moved our office and living quarters to Luray, Virginia. Meanwhile the number of our design engineers and field survey crews continued to increase. Following our move to Luray we returned to our surveys from where we had left them when moving from Skyland. I believe the remaining five or six miles northward to Panorama were the most difficult of all of my five years experience on the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway.

On a typical day we travelled ten miles by truck before dawn from Luray to Panorama (Elevation: 2,300 feet), where we left the truck for our return in the evening. We then traveled on foot to the south over the Appalachian trail which took us over Mary's Rock at an elevation of 3,500 feet, in a horizontal distance of about one-half mile. That amounted to an average climb of about one foot for every two feet of horizontal distance between those two points. Also, the Appalachian Trail in that area was not a constant graded path. It was over boulders and other irregularities sometimes as much as four feet or so. We had to crawl in places and sometimes be assisted by others in the group. Usually we had to stop once or twice going up or down as our knees would get too weak to hold up the weight of our bodies. As usual we had to carry our equipment and supplies too. From Mary's Rock we continued over the Trail to the south as much as three to five miles till we neared the place of our new day's work assignment. We then walked down the side of the mountain to where our new day's work would begin.

At the close of work each day, we retraced our steps up the side of the mountain and over the trail via Mary's Rock to Panorama by dusk, for the ten mile truck ride to Luray.

It should be noted that field engineering work such as outlined above under a "typical day" had to be repeated numerous times as required prior to, during and after the various stages of design and construction.

We encountered a variety of wild life while working on the Skyline Drive and Parkway projects which included deer, snakes, and occasionally bob cats and black bear. The deer presented no problem and the bob cats were seldom bothersome if left undisturbed. If black bear happened to be nearby we kept a careful eye on them for safety sake as they could quickly cause serious problems, especially if there was a cub along. They could be very demanding and were nothing to play with. They seldom disturbed our lunches which we carried in metal lunch pails, but if we happened to have any left over food following lunch we soon learned to dispose of it, just in case.

The snakes were one of our biggest problems and a constant threat except during the late fall and winter months when they went underground until spring. They were mostly Copperheads and Rattlers, being as much as five to seven feet long with the main part of their bodies being almost the size of a man's forearm. As we approached a rattler it would usually warn us with it's rattles and maybe move away but the copperheads would lay quietly coiled and wait for someone to get within striking distance. We considered them much more dangerous. When we knew of a snake being nearby, we would always give it a chance to move away but some were quite stubborn and we killed one or more most every day during the summer season. For protection from snake bites we wore high top leather boots over extra socks. I don't recall any of the men being harmed by a snake biting through those boots but there were a couple of occasions when they attempted to and left their fangs caught in them which was just a little too close for comfort.

In late fall a few miles south of Panorama, a power shovel was operating in an area of the proposed roadway where there was hardly any soil but a lot of course rocks. Much to everyone's surprise the shovel came up with a scoopful of those rocks along with many snakes from beneath the surface where they had made a den for the winter. In his excitement, the operator stopped the shovel with the scoop in midair and snakes were dangling in all directions. I happened to witness the episode and I never before nor since have seen so many snakes in one batch. One snake traveled down the shovel boom onto the operator's platform. As I recall there were about eight or ten workers in the immediate area and I believe both men and snakes were about equally frightened trying to get out of harm's way. When the excitement was over no person was harmed and most of the snakes made to safety. However, the shovel operator scrambled off the rig, walked off the job and didn't return.

When establishing a center line control over top the mountain ridge under which the proposed roadway tunnel just south of Panorama was being planned we stopped for lunch directly on that ridge. After lunch our party chief decided to lay with his head on his folded jacket on a bed of leaves at the base of a large boulder for a short rest. He had just gotten comfortable when he heard a slight rustle in the leaves. Turning his head to look, he found himself staring into the face of a copperhead snake coming from under the boulder. Luckily, the chief came up from there in a flash unharmed and we killed the snake.

By the latter part of 1932 construction of the Skyline Drive between Big Meadows end panorama was well underway and the first official opening of the Drive was held at Panorama on October 22, 1932. It was opened for a distance for fifteen or twenty miles to the south, over an unpaved base course material.

I continued working in the Luray and Front Royal, Virginia areas for a year or so and then transferred to work at various locations in the Park area as far south as it's termination at Waynesboro, Virginia.

I was next assigned to a number of locations on the Blue Ridge Parkway south from Waynesboro, Virginia as far as Black Mountain, North Carolina, when I transferred to other U. S. Government civil engineering work in December, 1935.

William M. Austin was the Engineer in Charge of the engineering design and contract construction of the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway projects. He was a very capable engineer and knew the work well. He, along with one man assisting walked over the greatest part of the route for the drive through those mountains in Virginia, establishing the preliminary rough grade and alignment limitations that basically provided the most beautiful scenic route for the Skyline Drive. The field survey parties followed over the many miles of the selected route obtaining the necessary engineering data required for the preparation of the preliminary and final design and construction plans which when completed provided for the contract construction of that most beautiful scenic Drive.

I hope you enjoyed my preceding article relating to the origin of the Skyline Drive and to some of my experiences while helping to bring it into being during that five year period.

I spent the next five years working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on topographic and hydrographic engineering on the eastern shore of Maryland and Virginia, the latter part of which I spent on the construction of the National Airport adjacent to Washington, D.C.

The following twenty-five years I worked with the Navy's Facilities Engineering Command. There, for the most part I supervised the preparation and updating of civil engineering design criteria as used for design and construction of the Navy's Shore Establishment Projects throughout the U.S. and Foreign Port Areas. These criteria were also used by private contractors as well, when involved.

Upon completion of thirty-five years of U.S. Government service in Civil Engineering work, I retired from the U.S. Navy's Facilities Engineering Command on December 31, 1966.